National Cancer Registry of Pakistan: First Comprehensive Report of Cancer Statistics 2015-2019

By Aamer Ikram1, Shahid Pervez2, Muhammad Tahir Khadim3, Muhammad Sohaib4, Hafeez Uddin5, Farhana Badar6, Ahmed Ijaz Masood7, Zafar I. A. Khattak8, Saima Naz1, Tayyaba Rahat1, Nighat Murad1, Farah Naz Memon1, Sumera Abid1, Faiza Bashir1, Ibrar Rafique1, Muhammad Ayaz Mustafa1, Roshan Kumar1, Aisha Shafiq4Affiliations

doi: 10.29271/jcpsp.2023.06.625ABSTRACT

Objective: To compile a comprehensive national cancer registry report of Pakistan by merging and analysing cancer registration data received from major functional cancer registries in various parts of Pakistan.

Study Design: Observational study.

Place and Duration of the Study: Health Research Institute (HRI), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Islamabad, from 2015-2019.

Methodology: Data from major cancer registries which included ‘Punjab Cancer Registry (PCR), ‘Karachi Cancer Registry (KCR)’, ‘Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) Cancer Registry’, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) Cancer Registry, Nishtar Medical University Hospital Multan (NMH), and Shifa International Hospital, Islamabad (SIH) registries were pooled, cleared, and analysed at HRI.

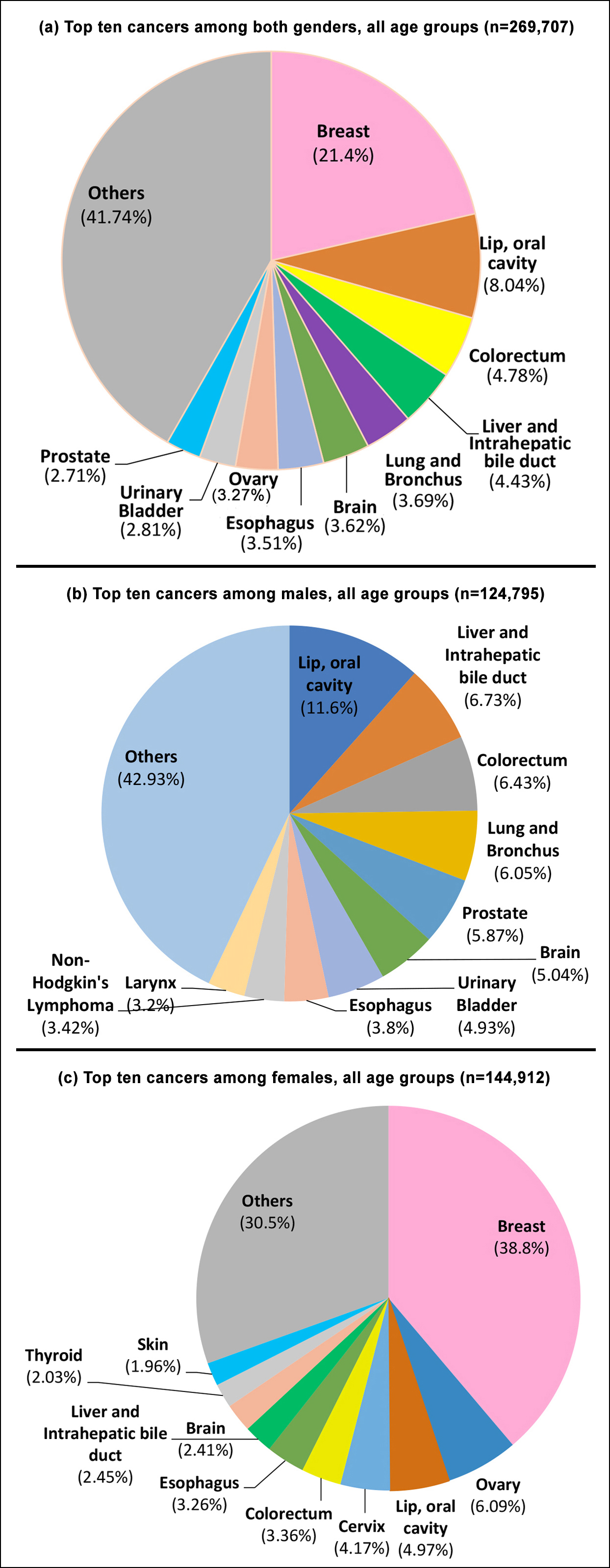

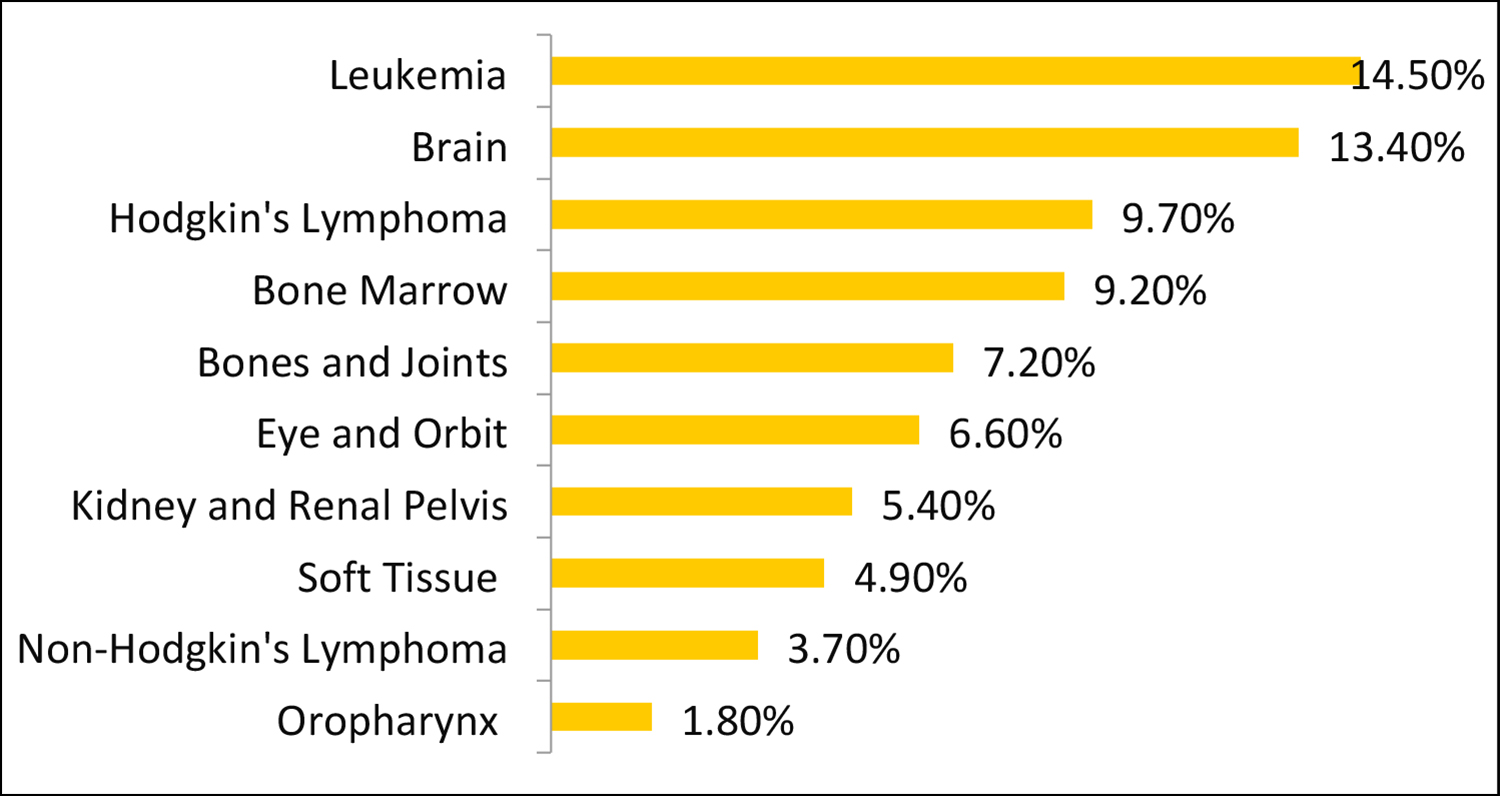

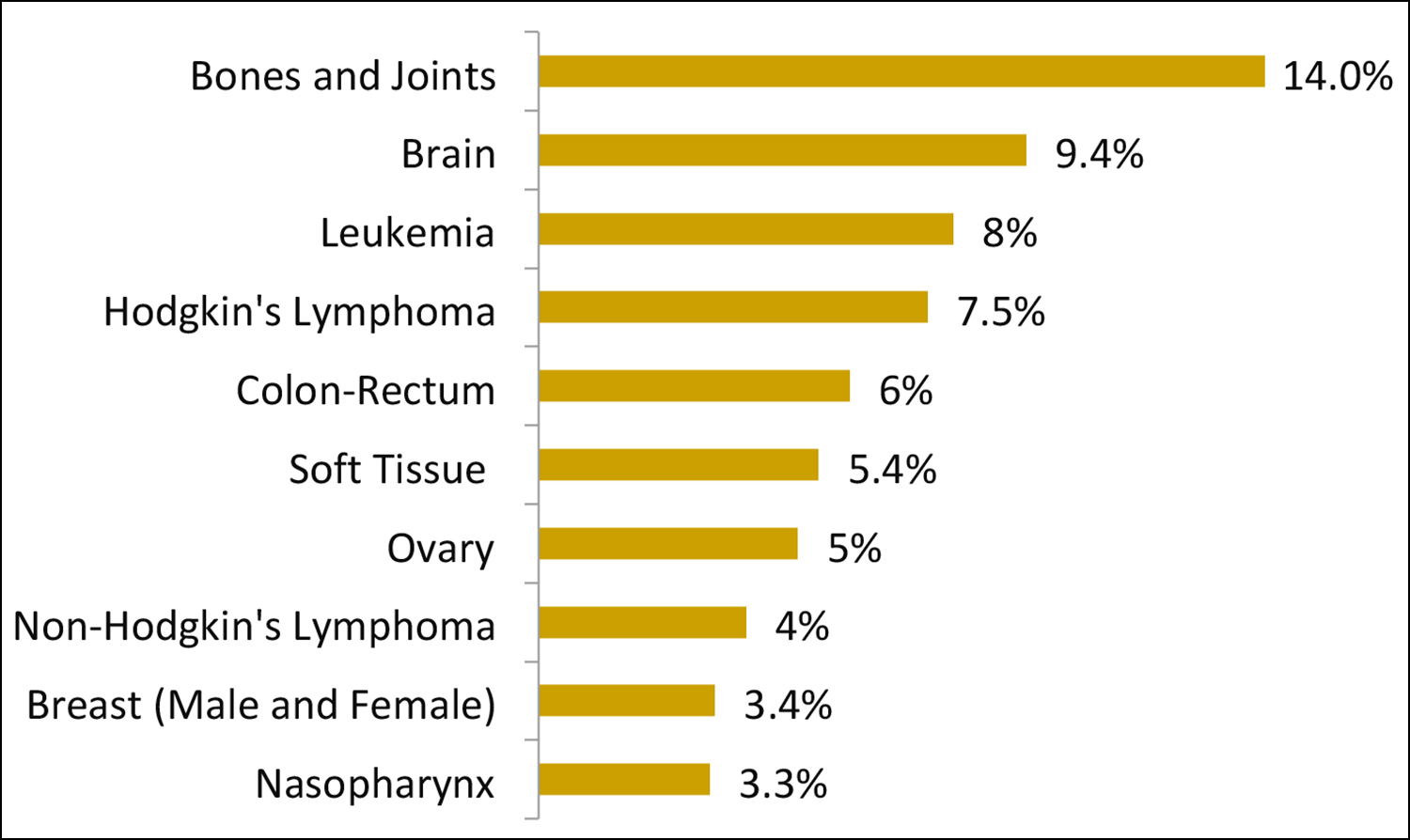

Results: A total of 269,707 cancer cases were analysed. Gender-wise 46.7% were males and 53.61% were females. As per province-wise distribution, 45.13% of cases were from Punjab, 26.83% from Sindh, 16.46% from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), and 3.52% from Baluchistan. Both genders combined, ‘breast cancer’ 57633 (21.4%) was the most common cancer. In males, the top-5 cancers in order of frequency/percenatages were ‘oral’ 14477 (11.6%), ‘liver’ 8398 (6.73%), colorectal 8024 (6.43%), ‘lung’ 7547 (6.05%) and ‘prostate’ 7322 (5.87% cancers). In females, causes of the top-5-cancers included ‘breast’ 56250 (38.8%), ‘ovary’ 8823 (6.09%), ‘oral’ 7195 (4.97%), ‘cervix’ 6043 (4.17%), and ‘colorectal’ 4860 (3.36%) cancers. In children ‘Leukemia’ 1626 (14.50%) and in adolescents ‘Bone’ 880 (14%) were the leading malignancies.

Conclusion: Breast cancer is the most common cancer in females touching epidemic proportions while ‘oral cancer’ which is the leading cancer in males ranks third in frequency in females. Like ‘oral cancer’ which shows a strong correlation with chewing, other common cancers in Pakistan including liver cancer, lung cancer, and cervical cancer are also largely preventable as showed a strong correlation with hepatitis B and C, smoking, and high-risk human papillomavirus.

Key Words: National Cancer Registry, Health Research Institute - NIH, Islamabad, Pakistan.

INTRODUCTION

Pakistan presently comprises of four provinces with Punjab being the most populous (53% population), Sindh next (24% Population), KP (15% population) and Baluchistan (6% population) in addition to Islamabad capital territory, Pakistan administered Kashmir, and Gilgit-Baltistan.

Pakistan is a low-income developing country with a GDP of US$ 376.49 billion and a per capita income of US$ 1658 (177th worldwide). The current life expectancy is 67.79 years while 64% are younger than 30 years, with 29% aged between 15-29 years. Approximately 40% of Pakistan is urban with M: F approximately 1.033 i.e., 1033 males per 1000 females. Pakistan’s current GDP allocation on health is 3% about half of the minimum as per the recommendation of WHO.1

In the developed world, cancer is becoming the leading cause of death as life expectancy has increased and morbidity and mortality due to heart diseases has markedly reduced. However, presently, the major burden of cancer is seen in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Among these, Asia-Pacific or Indo-Pacific regions stand out since it is home for four out of the five most populous countries of the world namely China, India, Indonesia, and Pakistan. Many low-income countries in the Asia-Pacific region are still struggling to initiate and maintain reliable cancer registration and cancer registries as in addition to global data of cancer incidence, robust geographical data of cancer incidence or prevalence is also of utmost importance. This allows to estimate differences in different regions according to specific age groups, gender, socioeconomic status, and above-all lifestyle for predictive modelling of various types of cancers.2 Although individual patients may not get any direct benefit from such data, it is earnestly required by the health authorities, policymakers, health professionals, and researchers to study the risk factors in a particular geographic region and to develop strategies to overcome the challenges posed. Cancer data in turn helps to measure the success of efforts to control and manage cancer.

Population-based cancer registries collect information on all new cancer cases in a well-defined population, whereas an institution /hospital/pathology-based cancer registry is an important way of verifying and registration of cancer clusters. Information regarding the geographical distribution of cancer provides better insight to understand the type and aetiology or risk factors. In most developed countries, this incidence is derived from population-based registries.

Like most other developing countries, the cancer incidence is increasing in Pakistan with only a few functional regional cancer registries.3 In the present situation inference can also be drawn from large-scale pathology or oncology-based cancer data at tertiary care centres. The important impediment in such data is the limitation to calculate the rate of incidence. However, with all its limitations, this type of data is important in completing the global picture of cancer distribution.4 National Cancer Registry data of Pakistan collected over a five-years period (2015-2019) from different cancer registries throughout Pakistan was analysed for the first time. The prime rationale was to formulate national policies, guidelines and strategic framework for cancer prevention and control. The objective of this study was to compile the relative frequency of various cancers as registered in the major registries across Pakistan.

METHODOLOGY

For compilation of a comprehensive report on cancer, statistics data were collected from registries. Each local registry was aligned with the international guidelines for cancer case finding and registration. Minimum dataset required for analyses included age, gender, date of first contact, primary site, and ICD coding. The cancer registries which contributed their data, included Punjab Cancer Registry (PCR), Karachi Cancer Registry (KCR), Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission Cancer Registry (PAEC), Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Cancer Registry (AFIP), Nishtar Medical University Hospital (NMUH), and Shifa International Hospital (SIH).5-9 PAEC is the major cancer service provider in Pakistan and runs 17 cancer service delivery centres termed ‘Atomic Energy Cancer Hospitals’ across the country, including all provinces and regions and shared its data for all 5-years. AFIP also shared 5-year data (2015-2019) which included biopsies not only originating from patients actively serving or retired from the Armed Forces but also from the Civilian population in particular covering northern Punjab and KP due to its state-of-the-art diagnostic facilities. PCR had 20 participating hospitals within Lahore and KCR had 08 participating centres at the time of data collection, both shared their 3-year data i.e., 2017-2019. NMUH from South Punjab and SIH from Islamabad shared their cancer data from 2016-2019 and 2018-2019, respectively. While PAEC and AFIP shared the data from 2015-2019.

Each registry uses customised software/data collection tools for the registration of cancer patients and collects information on different parameters according to their prerequisites and objectives. For the said report, common parameters were agreed upon by the National Steering Committee. Data Heterogeneity was removed by uniform coding of all data according to ICD-10. The codes assigned were reviewed by a Tumour Registrar and revisions were done accordingly. Confidentiality of patients’ data was maintained at all stages. The data were entered and analysed by using IBM-SPSS Statistics 20 software.

RESULTS

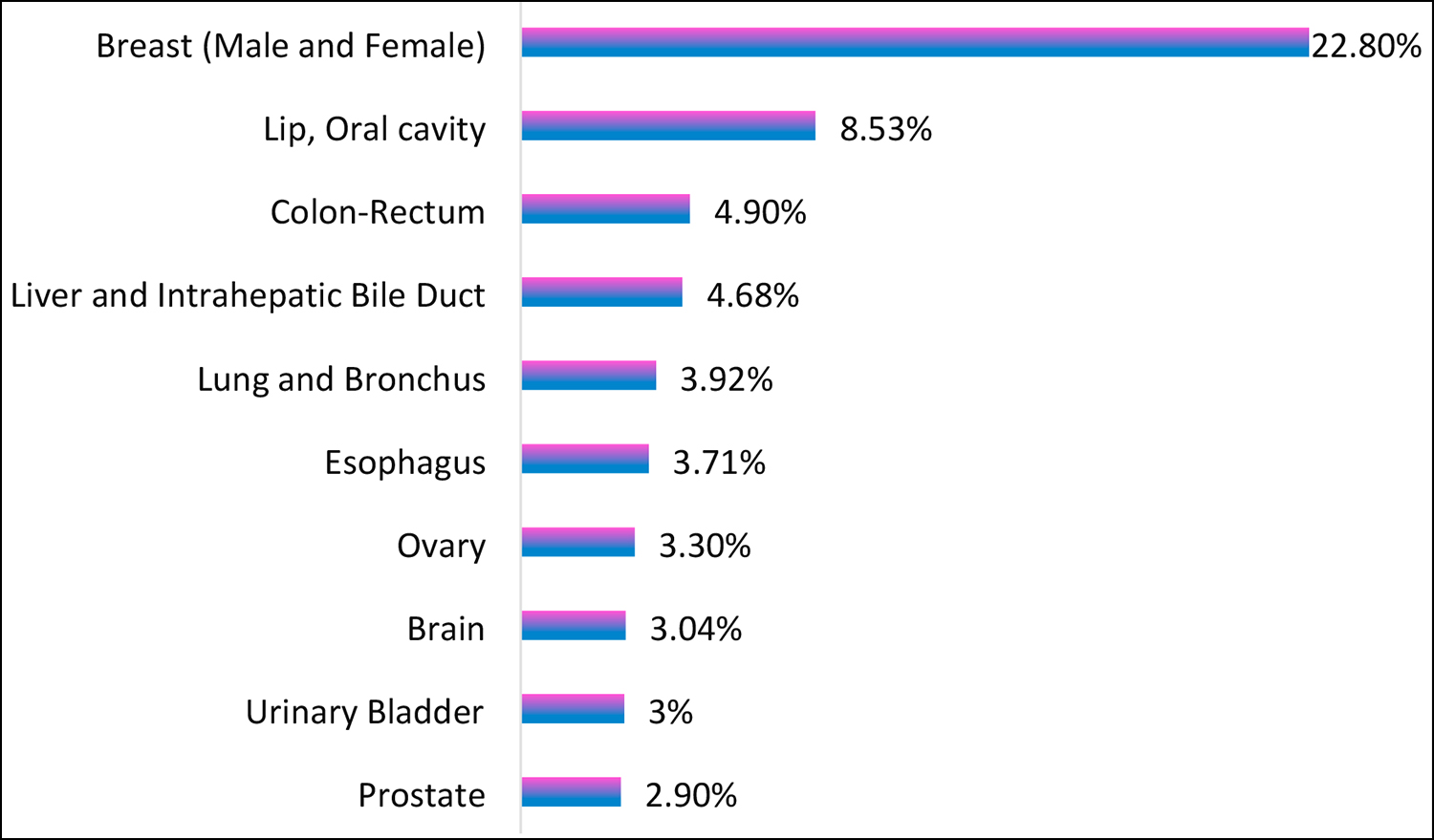

During the five years (2015-2017) a total of 269,707 malignant cases were received from six cancer registries including PAEC, AFIP, PCR, KCR, NMUH, and SIH, with 46.7% males and 53.61% females. As per province-wise distribution, 45.13% of cases were from Punjab, 26.83% from Sindh, 16.46 from KP and 3.52% from Baluchistan with 93.60% tumours in adults (≥20 years), whereas 4.10% in children (0-14 years) and 2.30% in adolescents (15-19) years. Table I shows the frequency of all malignant neoplasms including top-ten cancers among all age groups both genders combined. Figure 1 shows frequency of top-ten cancers all age-groups, both genders combined (1a), males only (1b) females only (1c). Figures 2 and 3 show the frequency of top-ten cancers among children and adolescents, both genders combined. Figure 4 shows the top ten cancers among adults ≥20 both genders combined.

DISCUSSION

This is the first ever attempt to bring together all cancer registries and datasets from all over Pakistan to share their data with NCR under the auspices of NIH, Islamabad for further analysis and deduce a holistic picture towards cancer patterns in Pakistan. This initiative was taken by Pakistan Health Research Council (PHRC) upon direction of Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination Pakistan, now reorganised as HRI-NIH. As cancer is not a notifiable disease in Pakistan, case registration is done by a few population-based and hospital-based cancer registries on their own accord. Some of the registries (population-based) use both active and passive case-finding methods, while others (hospital-based registries) register patients who are getting treated there.

Frequency data of NCR presented here is revealing in a variety of ways. This confirms that breast cancer (BC) is a very frequent cancer in Pakistan, one of the highest in Asia. It is quite commonly seen in premenopausal women and diagnosis in their 30’s is not uncommon. It seems that both genetic and environmental factors must be playing a role.10

Figure 1: Top ten cancers among all age groups both genders (1a), males (1b), and females (1c).

Figure 1: Top ten cancers among all age groups both genders (1a), males (1b), and females (1c).

Figure 2: Top ten cancers among children, both genders (n=11, 79).

Figure 2: Top ten cancers among children, both genders (n=11, 79).

Figure 3: Top ten cancers among adolescents, both genders (n=6278).

Figure 3: Top ten cancers among adolescents, both genders (n=6278).

Figure 4: Top ten cancers among adults >20 both genders combined (n=252,250).

Figure 4: Top ten cancers among adults >20 both genders combined (n=252,250).

As per Pakistan demographic and health survey 2018, cousin marriages are extremely common across Pakistan reaching a proportion of 60-70%.11 This is over and above early marriages, particularly in rural Pakistan.12 These two factors on one hand restrict genetic pool diversity while on the other hand expand the childbearing age significantly with multiparity. As BC is a hormone-dependent cancer, others factor like obesity and consumption of buffalo or cow milk where hormonal stimulation is used indiscriminately to enhance milk production are postulated risk factors.13 This in the absence of any breast screening program over and above social taboo to share breast related symptoms with family results in late diagnosis at a higher stage. This is the major cause of very high breast cancer related morbidity and mortality in Pakistan.

Table I: Frequency of Cancers in both genders including children, adolescents, and adults.

|

ICD-10 Code |

Malignant Neoplasm |

Total Male |

Total Female |

Children (0-14) |

Adolescents (15-19) |

Adults (≥20) |

Overall Total |

|

C00-C06 |

Lip, Oral Cavity |

14477 |

7195 |

45 |

114 |

21513 |

21672 |

|

C07-C08 |

Salivary Glands |

1111 |

880 |

63 |

81 |

1847 |

1991 |

|

C09-C10 |

Oropharynx |

2671 |

1642 |

195 |

166 |

3952 |

4313 |

|

C11 |

Nasopharynx |

1477 |

621 |

129 |

207 |

1762 |

2098 |

|

C12-C14 |

Hypopharynx |

2047 |

2136 |

10 |

44 |

4129 |

4183 |

|

C15 |

Esophagus |

4745 |

4718 |

17 |

82 |

9364 |

9463 |

|

C16 |

Stomach |

3667 |

1834 |

16 |

29 |

5456 |

5501 |

|

C17 |

Small Intestine |

418 |

280 |

21 |

16 |

661 |

698 |

|

C18-C21 |

Colon-Rectum |

8024 |

4860 |

140 |

376 |

12368 |

12884 |

|

C22 |

Liver and Intrahepatic Bile Duct |

8398 |

3552 |

83 |

50 |

11817 |

11950 |

|

C23-C24 |

Gall Bladder and Extrahepatic Bile Duct |

1205 |

2015 |

2 |

2 |

3216 |

3220 |

|

C25 |

Pancreas |

1468 |

1042 |

2 |

15 |

2493 |

2510 |

|

C26 |

Other Digestive Organs |

215 |

163 |

2 |

15 |

361 |

378 |

|

C30-C31 |

Nasal Cavity, Middle Ear and Sinuses |

881 |

497 |

53 |

44 |

1281 |

1378 |

|

C32 |

Larynx |

3994 |

725 |

9 |

15 |

4695 |

4719 |

|

C34 |

Bronchus and Lung |

7547 |

2397 |

17 |

39 |

9888 |

9944 |

|

C33, C37-C39 |

Other Thoracic organs |

600 |

296 |

54 |

37 |

805 |

896 |

|

C40-C41 |

Bones and Joints |

3306 |

1996 |

803 |

880 |

3619 |

5302 |

|

C42.1 |

Bone Marrow |

2054 |

1175 |

1034 |

196 |

1999 |

3229 |

|

C42.0, C42.2-C42.4 |

Blood, Spleen, Reticuloendothelial System NOS, Hematopoietic System NOS |

850 |

559 |

94 |

104 |

1211 |

1409 |

|

C43-C44 |

Skin |

3890 |

2834 |

111 |

85 |

6528 |

6724 |

|

C48 |

Retroperitoneum/Peritoneum, Omentum and Mesentery |

325 |

321 |

35 |

14 |

597 |

646 |

|

C47, C49 |

Soft Tissue |

2647 |

1771 |

543 |

341 |

3534 |

4418 |

|

C50 |

Breast (Male and Female) |

1383 |

56250 |

27 |

213 |

57393 |

57633 |

|

C51-C52 |

Vulva and Vagina |

0 |

829 |

6 |

3 |

820 |

829 |

|

C53 |

Cervix |

0 |

6043 |

7 |

13 |

6023 |

6043 |

|

C54 |

Corpus |

0 |

2796 |

2 |

5 |

2789 |

2796 |

|

C55 |

Uterus not otherwise specified |

0 |

2610 |

1 |

16 |

2593 |

2610 |

|

C56 |

Ovary |

0 |

8823 |

185 |

318 |

8320 |

8823 |

|

C57-C58 |

Other Female Genital Organs |

0 |

924 |

8 |

48 |

868 |

924 |

|

C60 |

Penis |

54 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

54 |

54 |

|

C61 |

Prostate |

7322 |

0 |

5 |

2 |

7315 |

7322 |

|

C62 |

Testis |

2072 |

0 |

129 |

136 |

1807 |

2072 |

|

C63 |

Other Male Genital Organ |

62 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

57 |

62 |

|

C64-C65 |

Kidney and Renal Pelvis |

2673 |

1450 |

607 |

51 |

3465 |

4123 |

|

C66 |

Ureter |

36 |

13 |

1 |

0 |

48 |

49 |

|

C67 |

Urinary Bladder |

6149 |

1434 |

27 |

6 |

7550 |

7583 |

|

C68 |

Other Urinary Organs |

70 |

16 |

4 |

0 |

82 |

86 |

|

C69 |

Eye and Orbit |

1178 |

832 |

734 |

40 |

1236 |

2010 |

|

C70 |

Meninges |

230 |

333 |

33 |

7 |

523 |

563 |

|

C71 |

Brain |

6292 |

3471 |

1503 |

588 |

7672 |

9763 |

|

C72 |

Other Nervous System |

488 |

315 |

187 |

61 |

555 |

803 |

|

C73 |

Thyroid |

1265 |

2944 |

37 |

125 |

4047 |

4209 |

|

C37, C74-C75 |

Other Endocrine (including Thymus) |

624 |

445 |

163 |

55 |

851 |

1069 |

|

C81 |

Hodgkin's Lymphoma |

2629 |

1243 |

1085 |

472 |

2315 |

3872 |

|

C82-C86, C96 |

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma |

4264 |

2397 |

417 |

247 |

5997 |

6661 |

|

C90 |

Multiple Myeloma |

779 |

409 |

1 |

0 |

1187 |

1188 |

|

C91-C95 |

Leukemia |

3489 |

2021 |

1626 |

503 |

3381 |

5510 |

|

---- |

Others and unspecified Malignant neoplasms |

7719 |

5805 |

906 |

412 |

12206 |

13524 |

|

|

Total |

124795 |

144912 |

11179 |

6278 |

252250 |

269707 |

NCR pooled data further confirm oral cavity (OC) cancer to be the leading No. 1 cancer in males of Pakistan and number three in females. In contrast to KCR data, where it ranks second in females, it descended to third number in this large country-wide sample. This is quite understandable as a large population of urban Sindh in particular its capital Karachi is in the habit of chewing betel leaf, betel nut, and tobacco leading to a very high occurrence of OC.14 In contrast to breast cancer, this cancer is largely a preventable cancer as over 3/4th patients diagnosed with OC are habitual chewers.15 Other risk factors include smoking,16 poor oral hygiene, and undernutrition. Another rampant habit, particularly in the Pakhtun population of Karachi as well as two provinces of Pakistan i.e., KP and Baluchistan, is the consumption of a preparation termed ‘naswar’. This is prepared from green tobacco herbs which are dried in the sun in a mixture of lime, ash, and flavouring agents. This is thought to be a little less carcinogenic compared to the ingredients used with betel nut widely and easily available in readymade sachet forms popularly termed as ‘Gutka’. Naswar use is also highly popular in Afghanistan bordering the KP and Baluchistan provinces of Pakistan.17 Punjab the largest province of Pakistan is relatively free of this kind of habit. Presence of high-risk HPV was found to be very low (about 3%) in a large study on OC patients with chronic chewing history. It is hypothesised that keratosis i.e., thick layer of keratin in chronic chewers due to physical friction poses a physical barrier to the penetration of HPV.

Another common cancer is liver cancer which is associated with very high mortality with survival usually counted in months than years at the time of diagnosis. This is largely due to a very high prevalence of Hepatitis B and C in Pakistan.18

There was an unprecedented rise in colorectal cancer as the third most common in both genders combined and in adult males, and the fourth most common in adult females. Again, both genetic and lifestyle factors seem to be involved for the increased frequency of large bowel adenocarcinoma. Pathologists in Pakistan encounter a significant number of large bowel adenocarcinomas occurring in the age group of 20s and 30s. A large majority of these show a poorly differentiated signet ring type morphology at times indistinguishable from signet ring adenocarcinoma of the stomach.19 In addition, over the last 2-3 decades a paradigm shift is seen in dietary habits with exponential increase in the consumption of fast food particularly in the very young population of Pakistan, which may be responsible for this trend. 20

Lung cancer seems to have retreated in the last couple of decades as the fourth most common cancer in males from the 1st or 2nd most common cancer a couple of decades ago, though still a major health-related cause of morbidity and mortality.21 One major reason is the major shift in Sindh province towards smokeless tobacco for various reasons which include better social acceptability compared to smoking. This along with easy and relatively economical availability of chewing alternatives has largely given way to chewing as a more attractive form of addiction, shifting the frequency of cancer from lungs to mouth.

Prostate cancer which worldwide is largely mentioned as the most common cancer in males was relatively low in frequency. One plausible explanation may be a modest mean life expectancy which is at least 10 years less than the developed countries. This cancer risk increases with age as has been proved beyond any doubt.

Esophageal cancer is highly prevalent in both genders, especailly in the two western provinces of Pakistan namely KP and Baluchistan.22 Very similar prevalence is reported from adjacent Afghanistan and Iran. This is largely attributed to their lifestyle which includes excessive hot beverage intake, and excessive consumption of red meat including salted preserved meat on the face of little consumption of vegetables and fruits. High sand (Silica) content in flour and bread leading to subclinical injury to esophageal mucosa over a long period of time may be a contributory factor. In contrast to the developed world, a great majority of esophageal carcinomas in Pakistan and this region are of squamous cell type rather than adenocarcinomas secondary to reflux esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus.

NHL is another very common cancer in Pakistan particularly in northern Pakistan and a variety of environmental factors may be playing their role which probably includes indiscriminate use of fertilizers and pesticides as Pakistan is still an agriculture-based economy. Brain tumours were also a common occurrence in both genders. As there are hardly any established risk factors for this, this is largely attributed to biological random mutations.

In female-specific cancers, ovarian cancers are more common than cervical cancer. This is again a malignancy for which there are few known risk factors. Although in the developed world, cervical cancer is decreasing due to robust screening programs, as well as vaccination for high-risk HPV, no such program exists in most low-income developing countries like Pakistan. Efforts by the Government and NGOs are underway to secure free HPV vaccination via international philanthropists. Few studies done in Pakistan show a very strong correlation of high-risk HPV in particular HPV 16 followed by 18 with cervical cancer as is the case with the rest of the world.23

Childhood (0-14 years) and adolescent (15-19 years) cancers closely match worldwide pattern dominated by haematolymphoid, brain, bone, and soft tissue malignancies. These malignancies are usually characterised by distinct chromosomal abnormalities like translocations among many other genetic alterations which occur spontaneously and are largely non-preventable. A small percentage may be traced to qualify as hereditary. Role of epigenetics is also being investigated. As per age statistics in Pakistan, 45% of the population is under 18 years of age and 37% under 14 years of age. On the face of this demographics, where about half of the population of Pakistan fall in the category of children and adolescents, just 6.4% of all cancer cases seem to be an underestimate. This appears to be largely contributed by underreporting on one hand and lack of diagnoses or misdiagnoses on the other. Although most childhood cancers like leukaemia, and Hodgkin’s and Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are curable, optimum management differences between the high-income developed world and low-income developing world is very wide to a tune of 80% vs. 30%.24,25

Although there are several limitations noted during data collection and analysis, nonetheless still this report carries the strength of a presentable huge data on cancer statistics in Pakistan. One of the major limitations is that the data was collected retrospectively from participating registries and centres. Another major caveat is that not all centres shared data for all 5-years. This was for a genuine reason as KCR was only revived in 2017 after a gap of several years, so 2015-16 data was not available. PCR though was operational in those years also contributed 3-year data from 2017-19 to match KCR. In addition, data from various registries may have led to multiple registrations of the same cancer patient as CNIC (Central National Identity Number) was not used as a unique identifier. This issue was resolved to some extent by cross-checking the name, date of birth/age, and permanent addresses of the patients. Finally, there is a significant chance of under-reporting from KP and Baluchistan as no population-based or multi-site registries exist in those provinces and data received was only from Pakistan Atomic Energy Cancer Hospitals.

The increased number of cases reported by one province does not necessarily mean that the other provinces do not have those cancers. The reason could be under-diagnosis and under-reporting from those provinces. Another major reason may be that patients from one province seeking medical services from other provinces having better, easily available cost-effective services besides various other administrative reasons. This is particularly true for Baluchistan and KP as a good number of patients from these two provinces do travel to major cities of Punjab and Sindh like Lahore, Karachi, and Rawalpindi/Islamabad for search of more advanced cancer diagnostic and management facilities.

A major recommendation by the NCR steering committee is for the lawmakers to legislate in both federal and provincial assemblies cancer as a mandatory reportable event. This will be the only guarantee to bring Pakistan at par with minimal dataset requirements as expected by international agencies with age-standardised incidence rates and it will be only from here that an effective cancer control program in Pakistan may be dreamed for.

CONCLUSION

Despite all inherent limitations and short-comings, NCR dataset is quite representative of what is being reported by regional cancer registries across Pakistan. Breast cancer is the most common cancer in females touching epidemic proportions while ‘oral cancer’ which is the leading cancer in males ranks third in frequency in females. This is also largely in conformity with WHO estimatation for Pakistan available on Globocan.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The authors sincerely acknowledge the contribution of the following individuals in various important capacities without which publication of this manuscript would not have been possible.

National Steering Committee of Cancer Registry:

Dr. Malik Muhammad Safi, Director Program Ministry of NHSR&C

Dr. Muhammad Faheem, Pakistan Society of Clinical Oncology

Dr. Ayesha Issani Majeed, Radiology Society of Pakistan

Mr. Shahzad Alam, Representative from WHO

Dr. Amjad Khan, University of Oxford, UK

Ms. Uzma Rizwan, System Director Cancer Services at CarePoint Health System, New Jersey, USA

Mr. Zeeshan Masood, Data entry operator PAEC

Karachi Cancer Registry:

Dr. Adnan A Jabbar, Aga Khan University Hospital & Ziauddin University Hospital, Karachi

Dr. Ghulam Haider, Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, Karachi

Dr. Muhammad Asif Qureshi, Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi

Dr. Shamvil Ashraf, Indus Hospital, Karachi

Dr. Fouzia Lateef, Ziauddin University Hospital, Karachi

Dr. Muhammad Khurshid, Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi

Dr. Imtiaz Bashir, Zainab Punjwani Hospital, Karachi

Dr. Manzoor Zaidi, Baqai Medical University Hospital, Karachi

Dr. Naureen Mushtaq, Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi

Dr. Zehra Fadoo, Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi

Dr. Mohammed Saeed Quraishy, Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi

Dr. Nausheen Yaqoob, Indus Hospital, Karachi

Mr. Ejaz Alam, Pakistan Health Research Council Research Centre, JPMC, Karachi

Dr. Huma Qureshi, Pakistan Health Research Council Research Centre, JPMC, Karachi

Punjab Cancer Registry:

Dr. Tariq Mahmood, Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Lahore

Dr. Usman Hassan, Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Lahore

Dr. Asif Loya, Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Lahore

Mr. Shahid Mahmood, Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Lahore

Dr. Tanveer Mustafa, Fatima Jinnah Medical University, Lahore

Dr. Asima Naz, Fatima Jinnah Medical University, Lahore

Dr. Muhammad Abbas Khokhar, King Edward Medical University and Mayo Hospital, Lahore

Dr. Raana Akhtar, King Edward Medical University and Mayo Hospital, Lahore

Dr. Alia Ahmad, University of Child Health Sciences and Children's Hospital, Lahore

Dr. Omar Rasheed Chughtai, Chughtai Institute of Pathology, Lahore

Dr. Aman-ur-Rehman, Sheikh Zayed Hospital, Lahore

Dr. Haseeb Ahmad Khan, Fatima Memorial Hospital, Lahore

Dr. Zeba Aziz, Hameed Latif Hospital, Lahore

Dr. Sana Afroze, Doctors Hospital and Medical Centre, Lahore

Dr. Ghulam Rasool Sial, Ittefaq Hospital, Lahore

Dr. Farooq Aziz, Shalamar Medical and Dental College, Lahore

Dr. Zahid Asghar, Doctors Hospital and Medical Centre, Lahore

Dr. Rakhshindah Bajwa, Services Institute of Medical Sciences, Lahore

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) Cancer Registry:

Dr. Nadeem Zafar, AFIP, Rawalpindi

Dr. Muhammad Asif, AFIP, Rawalpindi

Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC):

Mr. Zeeshan Masood, PAEC, Islamabad

Nishtar Medical University & Hospital Registry

Dr. Atique Anwar, NMUH, Multan

Dr. Sarah Khan, NMUH, Multan

Dr. Amna Khan, NMUH, Multan

Dr. Abdul Manan Jehangir, NMUH, Multan

Shifa International Hospital Registry:

Mr. Zafar Iqbal, SIH, Islamabad

Ms. Sumira Gulzar, SIH, Islamabad

Health Research Institute:

Dr. Arif Nadeem Saqib, Senior Research officer

ETHICAL APPROVAL AND PATIENTS' CONSENT:

Ethical approval and individual patient consent for cancer registries was taken by the respective hospitals sharing data and was almost always exempted by the respective Ethical Committees as identity of the individual patients was never revealed at any stage.

COMPETING INTEREST:

The authors declared no competing interest.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION:

AI: Provision of unique perspective and align the registries to achieve the goal.

SP: Concept, discussion, provide insight to data analysis and data shared.

MTK: Concept, introduction, provide insight to data analysis and data shared.

MS: Data shared (large scale).

HU, FB, AIM: Data shared and manuscript revision.

ZIAK: Data coding and data shared.

SN: Methodology, results and insight to data analysis.

TR: Data coding, data cleaning, data merging and data analysis.

NM: Manuscript revision and insight to data analysis.

FNM: Data coding and data management.

SA: Layout, planning and manuscript revision

EB, IR, MAM: Manuscript revision.

RK: Data compilation.

AS: Sharing from PAEC.

DISCLAIMER:

First twelve authors of this manuscript contributed equally irrespective of the sequence.

REFERENCES

- Burki SJ, Ziring L. "Pakistan". Encyclopedia Britannica, 31 Mar. 2023, www.britannica.com/place/Pakistan.

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021; 71(3): 209-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660.

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Pineros M, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer 2019; 144(8):1941-53. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31937.

- Idrees R, Fatima S, Abdul-Ghafar J, Raheem A, Ahmad Z. Cancer prevalence in Pakistan: Meta-analysis of various published studies to determine variation in cancer figures resulting from marked population heterogeneity in different parts of the country. World J Surg Oncol 2018; 16(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1429-z.

- Punjab Cancer Registry: https://punjabcancerregistry.org. pk.

- Pervez S, Jabbar AA, Haider G, Ashraf S, Qureshi MA, Lateef F, et al. Karachi cancer registry (KCR): Age-standardised incidence rate by age-group and gender in a mega city of Pakistan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2020; 21(11):3251-8. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.11.3251.

- PAEC cancer registry report 2015 - 2017 and 2018 - 2019. https://paec.gov.pk/Documents/Medical/PAECR_report_2015-17.pdf. https://paec.gov.pk/Documents/Medical/PAECR_report_2018-19.pdf

- Khadim MT, Jamal S. Cancer data statistics: AFIP monograph (fourth edition) review. Pak J Pathol 2018; 29(4):60.

- Cancer registry report 2018-2020 by Shifa International Hospital. http://www.shifa.com.pk/wp-content/uploads/2023/ 01/cancer-registry-report-27-12-2022-1.pdf

- Basra MA, Saher M, Athar MM, Raza MH. Breast cancer in Pakistan a critical appraisal of the situation regarding female health and where the nation stands? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2016; 17(7):3035-41. PMID: 27509926.

- Iqbal S, Zakar R, Fischer F, Zakar MZ. Consanguineous marriages and their association with women's reproductive health and fertility behavior in Pakistan: Secondary data analysis from demographic and health surveys, 1990-2018. BMC Women’s Health 2022; 22(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s12 905-022-01704-2.

- Melnik BC, John SM, Carrera-Bastos P, Cordain L, Leitzmann C, Weiskirchen R, et al. The role of cow's milk consumption in breast cancer initiation and progression. Curr Nutr Rep 2023; 12(1):122-40. doi: 10.1007/s13668-023-00457-0.

- Mubarik S, Wang F, Fawad M, Wang Y, Ahmad I, Yu C. Trends and projections in breast cancer mortality among four Asian countries (1990-2017): Evidence from five stochastic mortality models. Sci Rep 2020; 10(1):5480. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62393-1.

- Anwar N, Pervez S, Chundriger Q, Awan S, Moatter T, Ali TS. Oral cancer: Clinic pathological features and associated risk factors in a high-risk population presenting to a major tertiary care center in Pakistan. PLoS One 2020; 15(8):e0236359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236359.

- Pervez S, Abro A. Oral cancer and chewing habits. Development Oral 2017: 115-32. doi 10.1007/978-3-319- 48054-1_8.

- Abro B, Pervez S. Smoking and oral cancer. Development Oral Cancer’ Al Moustafa ed’ Springer 2017:49-59: doi 10. 1007/978-3- 319-48054-1_8.

- Khan Z, Suliankatchi RA, Heise TL, Dreger S. Naswar (smokeless tobacco) Use and the risk of oral cancer in Pakistan: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res 2019; 21(1):32-40. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx281.

- Hafeez Bhatti AB, Dar FS, Waheed A, Shafique K, Sultan F, Shah NH. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Pakistan: National trends and global perspective. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2016; 2016:5942306. doi: 10.1155/2016/5942306.

- Aitchison A, Hakkaart C, Whitehead M, Khan S, Siddique S, Ahmed R, et al. CDH1 gene mutation in early-onset, colorectal signet-ring cell carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract 2020; 216(5):152912. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2020.152912.

- Li L, Sun N, Zhang L, Xu G, Liu J, Hu J, et al. Fast-food consumption among young adolescents aged 12-15 years in 54 low- and middle-income countries. Global Health Action 2020; 13(1):1795438. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2020. 1795438.

- Sheikh SS, Munawar KM, Sheikh F, Qamar MFU. Lung cancer in Pakistan. J Thoracic Surg 2022; 17(5):602-7. doi: 10. 1016/j.jtho.2022.01.009.

- Ishaque SM, Achakzai MS, Ziauddin, Pervez S. Correlation of predisposing factors and esophageal malignancy in high-risk population of Baluchistan. Pak J Med Sci 2022; 38 (3Part-I):682-6. doi: 10.12669/pjms.38.3.4612.

- Raza SA, Franceschi S, Pallardy S, Malik FR, Avan BI, Zafar A, et al. Human papillomavirus infection in women with and without cervical cancer in Karachi, Pakistan. Br J Cancer 2010; 102(11):1657-60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605664.

- Fadhil I, Soliman R, Jaffar S, Al Madhi S, Saab R, Belgaumi A, et al. Estimated incidence, prevalence, mortality, and registration of childhood cancer (ages 0-14 years) in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region: An analysis of GLOBOCAN 2020 data. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2022; 6(7):466-73. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00122-5.

- Sohail Afzal M. Childhood Cancer in Pakistan. Iran J Public Health 2020; 49(8):1579. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v49i8.3908.